|

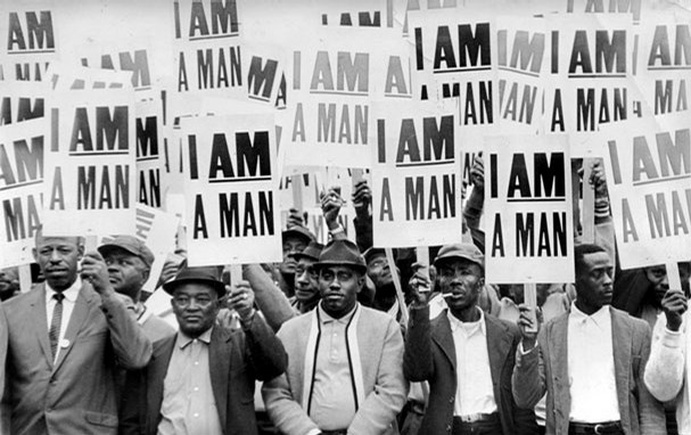

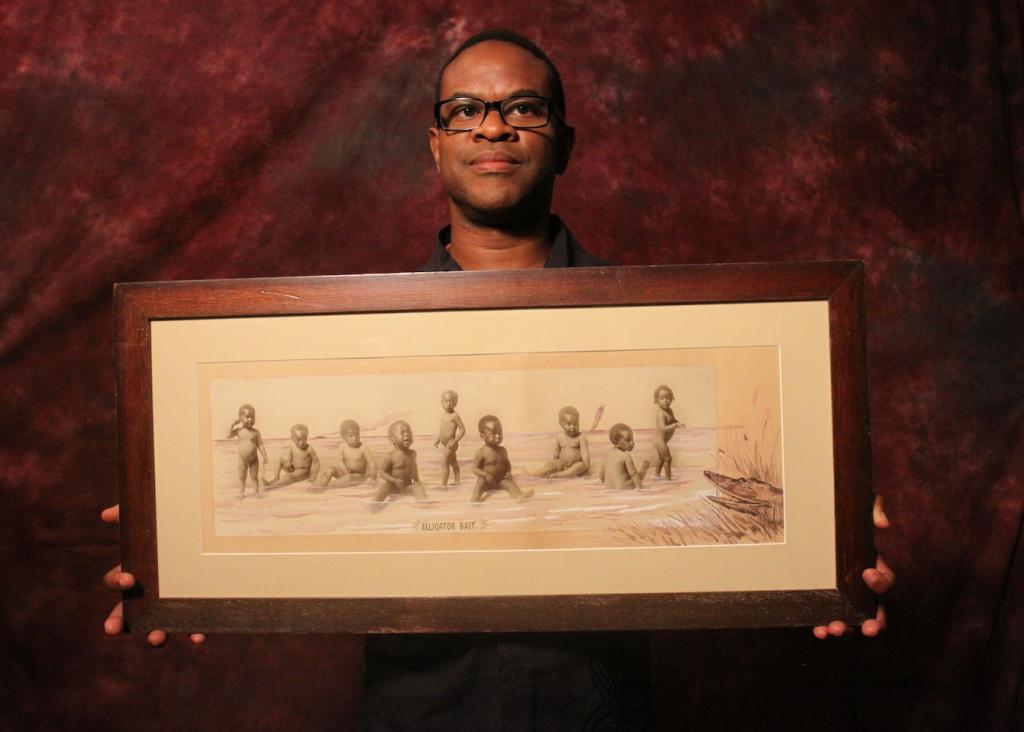

Last night I finally got a chance to attend the 38th-annual Atlanta Film Festival, a week-long event where buzzy independent films, shorts and movie projects are screened at Atlanta's oldest operating cinema, the Plaza Theatre. I missed quite a few showings I really wanted to see (potty training a toddler makes your social life crappy in more ways than one), but catching the photo-documentary Through A Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People made up for everything I didn't get to see. Here's why you too should see this really cool project when it comes to your town. Indie films--especially documentaries--don't always deliver. Good intentions have paved the way to many a hell-spawned production. I say that meaning no disrespect to those who show the will and perseverance it takes to create such works, which I haven't yet mustered up, making my opinion a humbled one. Still, some of that shit sucks. I don't have to be a professional dancer to appreciate Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and I don't have to be a hair stylist to know that Pam Oliver's weave is consistently atrocious. It is what it is. On the other hand, sometimes you are pleasantly surprised by a bright new idea in any format, especially when its being brought to you in visual form. In the case of Through A Lens Darkly, the audience receives a wonderful gift in the form of a photographic tour of African-American life, its ongoing history and documentation. The film, produced in part by Deb Willis (writer of Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present), centers around black photographers such as James VanDerZee, Carrie Mae Weems and Gordon Parks. It exposes the relationships between these photographers and the families and individuals who were their clients and customers, and it studies and challenges others to join an archiving of images that capture black Americans in honest moments recognizable to all as familiar and human. The film's creator, Thomas Allen Harris, is a Harvard grad who uses his own family photography as the story's roux, creating an extended visual portrait of the national black family. The result is a loving and appreciative take on photos' ability to tell unbreakable truths--even when abrasive and sometimes difficult cultural imagery must be captured and shared. During the doc's 90 minute showtime, we see the proud and determined focus shown in poses taken by Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, each of whom deeply understood the power of the photo to present a face of dignity in a time when such a word had little to no meaning to many African-Americans. We also see heartbreaking funeral photography of Emmett Till, and shots of the era in which blackface, lynchings, cartoonish drawings of menacing and imbecilic blacks lusting for watermelons/chickens/white women, and other fear-mongering tactics were employed by various factions of society. Perhaps most potent is the film's statements on the reflective nature of great photography, and how connections based on identity and love can be generated simply by viewing honest images of a people on the course to establishing themselves as equal citizens in a country that still sometimes denies full recognition to those who not only were giving this right at birth, but who've sometimes been forced to work incredibly hard to earn it.  Image Credit: Ernest Withers This film comes at a crossroads in terms of citizen and professional journalism. In 2013, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer John H. White was laid off by his employer, Chicago Sun-Times. Journalists at the paper who survived the cuts were apparently asked to use smartphones fixed with high-resolution cameras, to collect images while reporting. In other words, photographers who had spent their lives perfecting a craft as simple and important as capturing rare images for stories were no longer necessary to the finished product, since they were ultimately cutting into the bottom line of profitability. Pretty stupid, especially when you think about the fact that most people don't read actual text anyway--they look at the pictures. Even online.

T.A.L.D. ultimately hits a positive nerve for the black community, and provides a takeaway that could result in a wonderful national project if people see the film and get involved. Watching it, you're reminded that we're all inherently similar, and the struggles of black Americans are inherently American, whether the subjects are slaves, freed men and women, icons, gangsters, political and spiritual leaders, or just kids being kids. Black kids. American kids. All this to say, check it out. It'll open in NY this summer, and'll be back in Atlanta for the Bronze Lens Film Festival in November. *Main image credit: Pan African Film Festival

1 Comment

AuthorThis is where Michael B. Jordan shares his thoughts on the world with the world. Share yours back. Archives

September 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed